The importance of having an ethical approach to the way that you apply analytics seems to be getting increasing focus. But given the significant amount of press coverage that the subject is getting and the potential for significant reputational damage there seems to be surprisingly little in the way of guidance about for what is and isn’t appropriate.

Why is it important to have an ethical approach? Firstly there is a potential for serious reputational damage for failing to do so. Secondly there is the potential for increased legislation or regulation in this area.

What constitutes unethical behaviour? Much of the discussion seems to focus on breaches of individual privacy, and what expectation of privacy people should expect. But breaching privacy isn’t the only way that analytics can breach what many people would consider to be acceptable behaviour. Judging by some of the recent news stories in this area:

- is it acceptable for Target to predict the likelihood that a customer is pregnant?

- for Amazon to charge different prices to different customersbased on personal history?

- for store loyalty card data to be used to cross-sell health insurance?

To be clear, that final example is a hypothetical one, but one that’s not so far away from some real life examples, as I will discuss later.

The common theme in these stories, as well as various others that consider the potential for breaching individual privacy, is the “yuk-factor” – the potential to immediately and instinctively alienate customers and potential customers. One of the dilemmas for organisations considering whether to proceed with applications of analytics like these is how open to be about it, and the default position has frequently been to avoid exposing to much detail, partly because of the potential for competitive advantage but partly to avoid alienating consumers.

A lot of organisations are wrestling with these types of ethical questions. I recently took part in a procurement process for the application of predictive analytics by public sector organisation. As part of the procurement I had to present to the client staff responsible for the ethical considerations and answer a selection of tricky questions: (how we would use the data and analytics to improve their service? how would we handle the potential for unfair discrimination?).

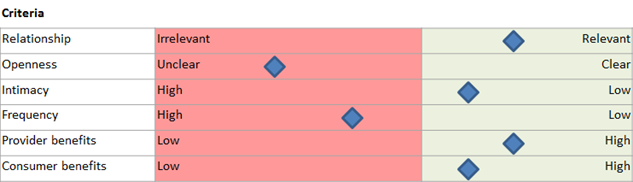

What’s lacking as far as I can tell is any sort of framework for judging what is and isn’t appropriate. So, what I am going to try to do is set out the criteria we can use to judge what is and isn’t appropriate behaviour. This is emerging thinking for me, so I may well revisit and revise this list over time (and I’d appreciate suggestions) but what I have so far is an assessment of six criteria:

The first three criteria all relate to the customer’s expectation:

Is what is being proposed appropriate to the Relationship between the two parties? For example, if I promote products closely related to the one’s I already sell you, then most consumers see this as appropriate or even beneficial. How far our relationship stretches, though, is debateable.

The technical requirements of Openness, such as a published privacy statement, are met by respectable organisations, but when it comes to applying this in practice there are different extremes. Telling me that I am being recommended X because I also bought Y is generally open, and something some find reassuring. Telling me that my friend has bought product X is certainly open too (though it might fail the intimacy criteria below). The opposite extreme is actually very common too. In the New York Times article I linked to above there’s a really interesting quote:

“With the pregnancy products, though, we learned that some women react badly,” the executive said. “Then we started mixing in all these ads for things we knew pregnant women would never buy, so the baby ads looked random. We’d put an ad for a lawn mower next to diapers. We’d put a coupon for wineglasses next to infant clothes. That way, it looked like all the products were chosen by chance.

“And we found out that as long as a pregnant woman thinks she hasn’t been spied on, she’ll use the coupons. She just assumes that everyone else on her block got the same mailer for diapers and cribs. As long as we don’t spook her, it works.”

On the face of it, this is the complete opposite of openness. And it’s not a unique insight of Target, because this is standard practice in a number of other retailers too. Is it ethical? It’s certainly manipulative and risks a backlash from some consumers if they realise what’s going on.

Intimacy is about the nature of the product or service being offered. This article has a nice model of the different types of intimacy in personal information, and makes the point that to use more intimate information a closer relationship is required. Retailers who use highly targeted advertising well tend to understand the different types of intimacy requirement in different product categories. The pregnancy example above highlights this in part. They do the same thing with pets: beware sending a promotion for cat food to a customer whose pet has just died.

Frequency is well understood by most marketing professionals too. There’s a limit to how often most consumers welcome contact, though it depends too on the strength of the relationship between the parties.

A lot of applications of customer analytics deliver direct Consumer benefits as well as more obvious Provider Benefits. For example, when they’re done well, recommender systems (“customers with your purchase history also bought these…”) are valued by customers as well as by providers; indeed when they’re done badly it’s often because it’s seen by the provider as merely an exercise in cross-selling rather than as something valued by the customer.

It’s easy to confuse provider and consumer benefits. Partly that’s because a provider benefit can be, indirectly, a consumer benefit too. Most consumers have at least a partial understanding that by providing personal information in a transaction they are providing something of value to the other party, but they’re doing so in return for either a reduced price (for example by using a customer loyalty card) or for a free service (as with many online services).

More disingenuous is to present a provider benefit as being of direct benefit to the consumer. It seems to be an article of faith for many of those engaged in online marketing that targeted advertising is a direct benefit to the consumer being served with the advertisement. It’s easy to see why better targeting is beneficial to the advertiser, but the benefit to the consumer is at best arguable and appears to be facing an increasing consumer backlash.

In the next part of this thread I am going to consider some real-life examples and how this framework applies.

Pingback: The ethics of pricing analytics? | Read me like a blog

Pingback: The ethics of analytics – another example | Read me like a blog